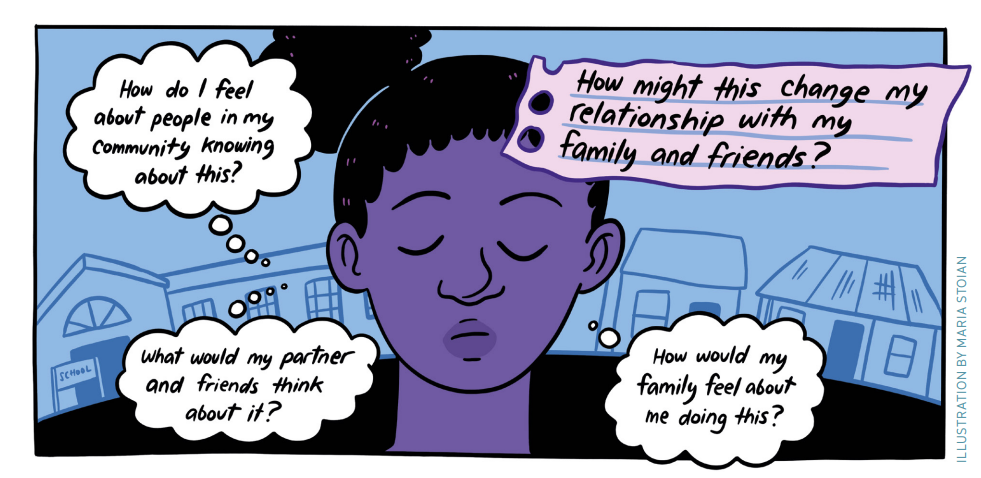

The initial scoping, planning, recruiting and training phases all contribute to building a safe space for children and young people to work together.

Before asking young people to explore topics that might be challenging to discuss openly, in the Our Voices programme, we have built in workshops and activities to create a space where people feel comfortable to discuss these topics.

The Creating a safe space: Ideas for the development of participatory group work to address sexual violence with young people includes lots of different activities and exercises to help you plan these initial sessions.

Through testing these out in different projects, we have documented how young people have found some of these different activities.

|

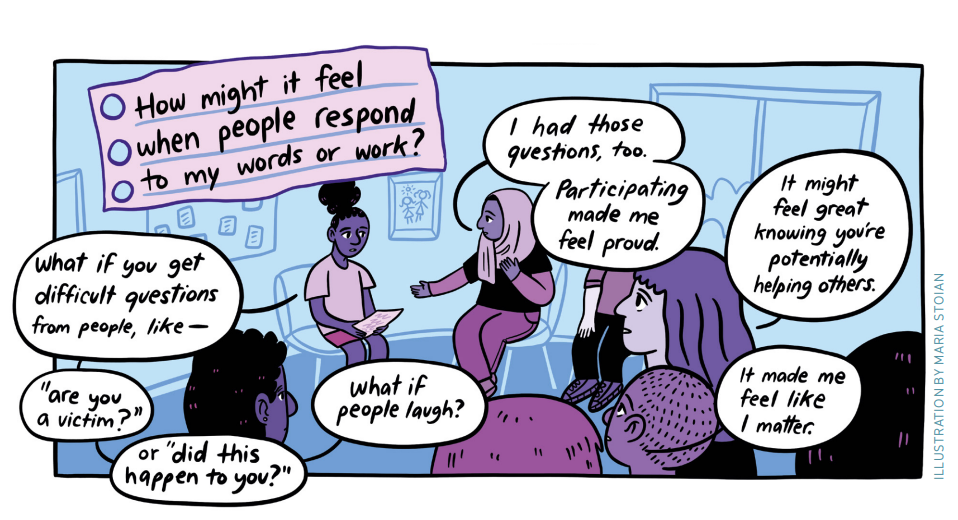

Practice example: Setting group ground rules in a creative project in Kenya and Uganda As part of the Our Voices III project, we worked with facilitating partners – Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL) and the Kenya Alliance for Advancement of Children (KAACR) – on a creative project entitled ‘Progressing Participation as Protection’. The aim of the project was to support dialogue between young people in different countries about the relationship between participation and protection rights in the context of child sexual abuse and exploitation (CSA/E). The project provided a platform to allow young people to share key messages about the value of participation, from their perspectives, with professionals and other young people.

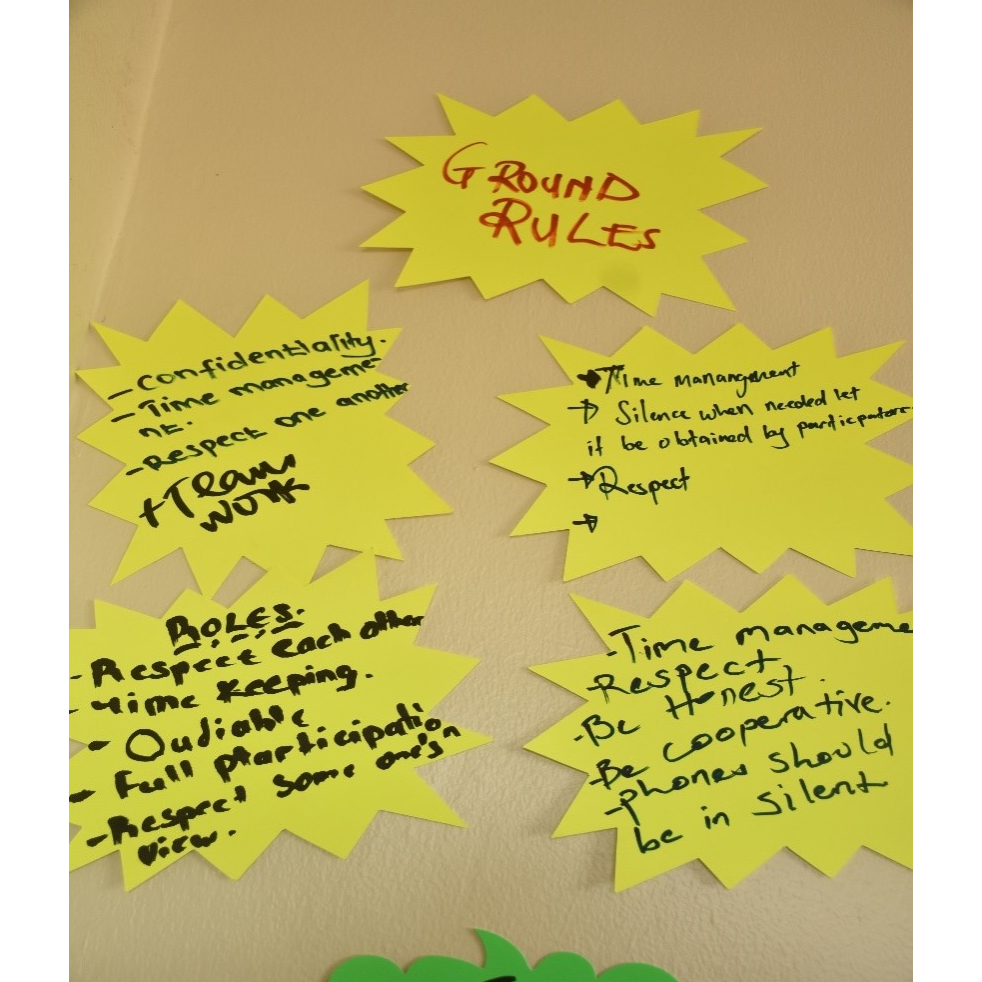

In order to implement this project, the Our Voices team at the Safer Young Lives Research Centre teamed up with our Young Researchers’ Advisory Panel (YRAP) to design a series of six workshops. These workshops included different activities that aimed to help young people reflect and consider what is positive about young people’s participation and develop some key messages to share with others. Once the workshop plans were created, these were then facilitated by our local partners in Kenya and Uganda. Nineteen young people, aged 17-25 years old (15 females and 4 males) took part in these workshops. During the process note-takers from each partner organisation captured how the young people engaged in the activities and recorded key discussions points. These activities provided a foundation for the young people to develop and curate key messages about this topic which were then audio-recorded for a podcast exploring the value of participation. In the initial workshops we included an activity for the group to set ground rules. This was taken from Creating a safe space: Ideas for the development of participatory group work to address sexual violence with young people it gives young people the opportunity to define how the group will operate throughout the workshops. The activity involves creating a simple agreement that outlines how the group will/won’t behave during their time together to help everyone feel safe. Group members can work in pairs or think by themselves about things they would like to include in the group agreement, including how they want the facilitator to behave. This might be things like ‘arrive on time’, or ‘respect other people’s views’. Everyone is then asked to share their ideas and the facilitator asks if the rest of the group understand and agree that this should be added to the list. If so, these are captured on flipchart paper. The facilitator may ask for clarification to make sure concepts are clearly understood – e.g. ‘what does respect mean?’ ‘how would we know if someone is being (dis)respectful?’. It’s also important to be realistic and mindful that although everyone may agree to a rule, such as ‘it’s important to be on time’, there may be things that get in the way and therefore it’s about trying to respect the rules as best as people can. It is also important to think as a group what will happen if rules are disregarded and whether for some of these rules a sanction should be in place if they are continuously broken. Once the agreement has been finalised everyone (including the facilitator) should mark or sign their names on the agreement. The idea is that each workshop will then begin with a reminder of this agreement and group members and the facilitator can refer back to them if they need to throughout the discussions. It was interesting to see that both groups came up with similar rules. These included rules around mobile phones being on silent; respect for privacy/confidentiality; full participation; respecting each other and each others’ views which included listening to each other. In Kenya the group also noted that young people should have a right to be silent and that the space should be free and happy. In Uganda the group talked about the importance of time management and team work.

Whilst the ground rules exercise is simple, some group members shared at the end of the project that having these rules helped them feel safe.

|