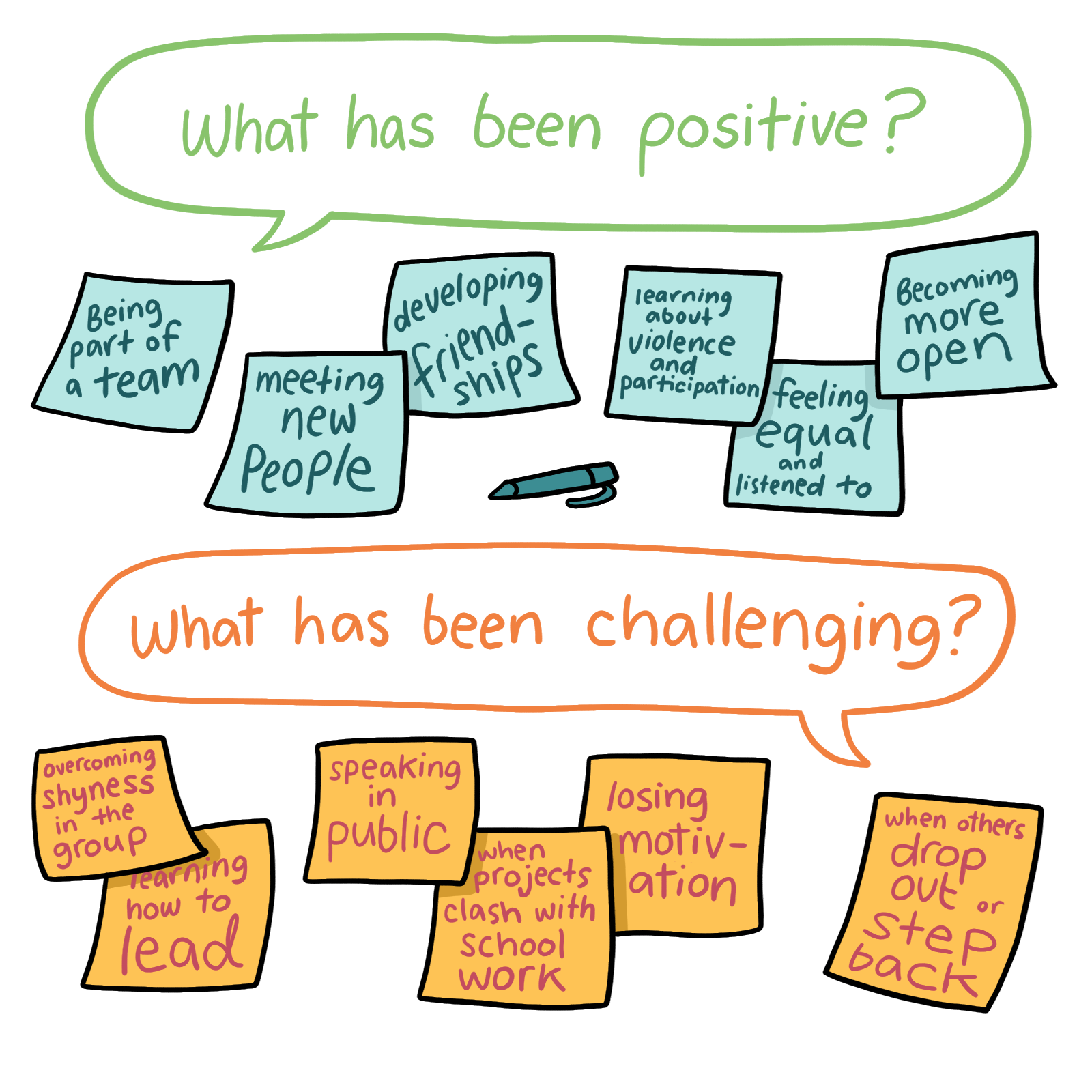

We have seen the importance of pausing, reflecting and documenting learning as new activities, tools and processes are tested.

We have also heard from those we have worked with (participants, partners and children and young people) that having the space to reflect, hear from others, and share learning can help them navigate current challenges they may be facing, spark innovation and support new ways of thinking.

|

Practice example: Ongoing reflection when developing peer mentoring programmes As part of the Our Voices Too project, we undertook a study to learn more about peer support for young people (aged 10–24 years) who had been impacted by sexual violence and how such initiatives work in practice. Twenty-five participants from 12 different organisations and initiatives, located in five countries, with experience of engaging in peer support initiatives for young people affected by sexual violence, took part in the study. Through this study we learnt about a number of challenges participants had encountered when setting up peer support models. Emphasis was placed on the importance of pausing to reflect on these challenges, and having space to adapt, and consider different solutions and strategies, to minimise the risk of challenges re-occurring. This research illustrated how critical reflection was a key strategy in keeping everyone involved safe. Read more about this aspect of critical reflection in the article ‘Keeping the informal safe’: Strategies for developing peer support initiatives for young people who have experienced sexual violence. |